Articles

Dealer’s Corner

A better interface – a proposal for preventing wet window frames

A proposal to prevent wet window frames.

October 15, 2018 By Jon Eakes

There are many variations on how to install a window into a wall, largely differing between new construction and renovation, but there is one almost universal principle presently in practice: stop both the water and the wind at the outer face of the crack between the wall and the window – the window/wall interface.

Many window manufacturers slide over the questions of installation, leaving that responsibility to the installer while staying as far away as possible from responsibility for work they cannot control. Often, on site, one person builds the wall, another applies moisture protection to the wall framing, a third attaches the window, a fourth applies insulation and perhaps a fifth attempts to seal the whole operation. Sloped sill supports are rare and shims are often simply left out because of the convenience of the mounting flanges. Even in cases where far more care and coordination takes place, windows tend to eventually leak. The best current efforts are centered on simply doing a better job of sealing out water.

I tend to work mostly in renovation and the golden rule of a window change-out is to pull out the whole frame, repair the water damage in the structure, then install the new window much like the old one was installed. But why do we accept rotten wood under or around windows as normal? Maybe there is a bigger problem than just poor workmanship.

With today’s building science knowledge and modern materials one would think we could find a way to install windows that are easy to get perfect in the field and provide permanent protection against water getting to any wood. Understanding the rainscreen principle, commonly used for both commercial and residential walls, and applying it to this narrow but so-vulnerable space between walls and windows might just be the key, allowing us to have leak-proof windows with no exterior caulking to age or be subject to poor maintenance.

That is the challenge I launched at FenCon18 last March. I based my drive for a way to apply this moisture control technology on two research projects published in 2011 and 2013 by the IRC (Institute for Research in Construction, part of the National Research Council of Canada). I began to look at why there is so little change in window installation despite significant failures, especially in colder climates. The primary conclusion of these two research projects was that you should not attempt to stop both the water and the wind on the same plane.

That has interesting ramifications. When we caulk on the outdoor side of a whole assembly, we break this rule right from the start. We flow water over caulking that was imperfectly applied (ever seen that?), or that is inadequately maintained, and then subject the water flowing over an open crack to the full force of the wind. You lose – the water is forced inward.

So why not simply accept that the outermost assembly of a window does no more than most siding? It sheds the major portion of rain but is not entirely responsible for waterproofing the installation.

Inside, we can make a far more effective moisture barrier by shedding water that gets through the siding and the window trim – again, without attempting to make it totally waterproof. We are not building with wishful thinking about perfect workmanship and perfect materials that never age or move. So although the wind is buffered by the siding, the wind pressure always gets behind the siding. Most facades are actually made to permit that to happen – it is called a rainscreen wall. So we get a reduced amount of water flowing over the window/wall interface with a slightly reduced wind pressure.

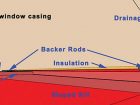

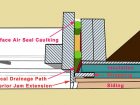

We can apply the rainscreen principle to the window/wall interface by leaving a small empty drainage path totally free and open behind the moisture barrier. This could be behind the mounting flange or, in the absence of a mounting flange, behind strapping that butts up to the window casing itself or even further back behind insulated sheathing that is not sealed. Behind this is a backer rod that controls where the insulation stops, leaving the drainage path free and open. At the bottom of the drainage path that flows down the sides of the window is an open and sloped waterproofed sill, directing any water to the outdoors.

But you are not done until you fulfill the other important element of a rainscreen: totally air-seal the window/wall interface on the inside of the window assembly. This creates a dead air space that will pressurize with any wind flowing up from below (without carrying any water) eliminating the driving force of the wind across the moisture barrier where the water has been stopped. Small imperfections in the moisture barrier will let very little water through and what does get past the barrier is not blown in further by the force of the wind but simply flows down to the sill region. There is no driving force on this water, it just drips out.

With modern elastomeric sheets or liquids we can easily waterproof the rough framing. With backer rod and caulking we can efficiently create a perfect air seal on the inside because of the indoor working conditions. With properly placed water shedding and open drainage paths we have a window installation that will permanently keep the house structure dry, with no maintenance.

There is a lot of discussion to have about the advantages of recessed glazing and the elimination of thermal bridging, and even just how much and what type of insulation we really need when we are working with dead air spaces. I am starting from the acceptance that all joints with both water flow and wind pressure have a high chance of eventually leaking. I feel that all moisture shedding joints should be arranged in a shingling fashion so that the actual seal is less important. We need definite clear drainage without air flow to carry water inward. Pressure equalization, to the extent it works, will help.

I have re-grouped with a growing number of manufacturers, consultants and researchers who are rising to my challenge with an ad-hoc prairie window interface committee. We have not perfected how to do all of this efficiently and economically as yet. Personally, I feel we will need more and better external jam extensions and the elimination of the window mounting flange – but that is not yet a consensus. This is a work in progress that came out of FenCon18 and I am sure will continue right up to FenCon19.

If you are interested in getting the links to the IRC research reports and to see a little video that attempts to visually demonstrate water, wind, air sealing and pressure equalization, go to my website: joneakes.com/trades-training and scroll down to the Window Installation drawer. At the bottom of that article there is a link for you to send me your comments or questions. Together we may actually make window installations as good as the windows we are installing.

Jon Eakes is a trades educator and communicator based in Montreal. He’s been talking construction in public since first appearing as CTV’s Mr. Chips in 1978.

Print this page

Leave a Reply