Articles

Technology

The problem with Passive House

Concerns around applying Europe’s gold standard for energy efficiency.

November 2, 2023 By Phil Lewin

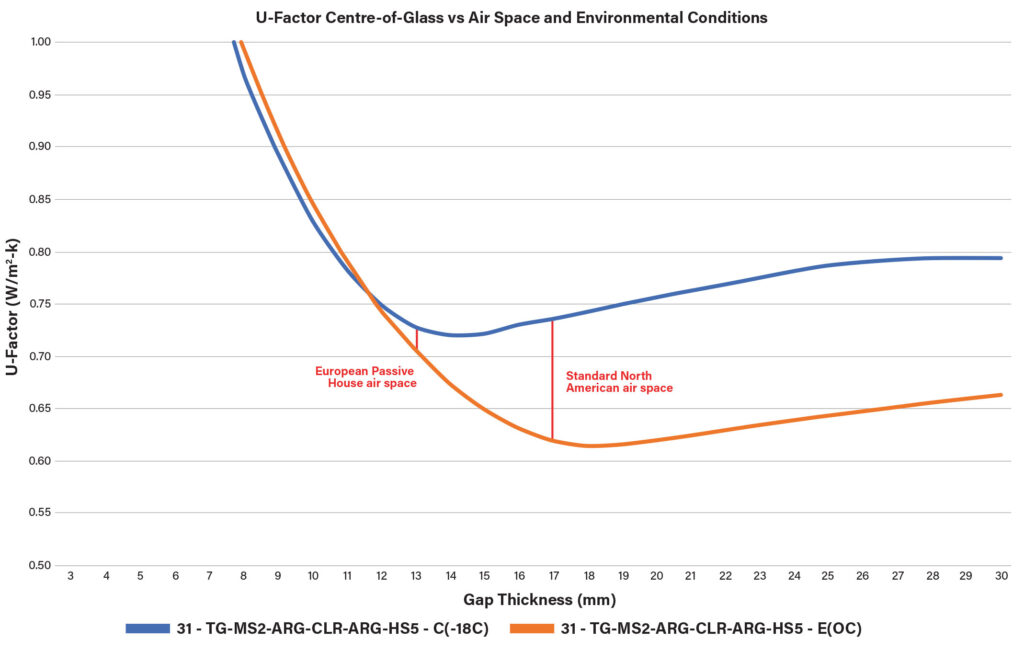

At 0 C (blue curve) the Passive House window performs better. At minus 18 (orange curve), a standard North American air gap retains a much higher U-factor. Because physics.

At 0 C (blue curve) the Passive House window performs better. At minus 18 (orange curve), a standard North American air gap retains a much higher U-factor. Because physics. One thing I like about my relationship with Fenestration Review is that I am not expected to be a reporter and stay neutral on issues I raise.

That is a good thing as I am a person with strong opinions. While in today’s article I have made every effort to air both sides of the issue, I am not without my own opinion as you will read.

I admit that as soon as I finish an article, I start worrying about what I can write about next time. For this issue I came up with a great idea! I asked my fellow members of the CSA A440.4 committee that has been busy making modifications to the installation standards for their thoughts as to what are the most significant issues facing the window and door industry in the near future. I received an excellent list of critical issues, however one jumped out and slapped me. To quote, “Then another issue we come up against is the lack of decent-performing windows in the North American market. Anything with decent insulation values is coming from Europe.”

What? I do not believe that European windows are intrinsically better than those manufactured in North America, so, what gives? After a little bit of direct communication with the source of this comment, it was clarified: the writer was referring to windows that could be used in the Passive House program. This did make sense to me, but it also brought up a level of frustration I incurred back when I worked in window manufacturing. At the time, a customer was trying to quote a Passive House specification in Canada, but couldn’t because my Canadian manufacturer had never tested to the required European standard.

As we had already spent what I would estimate to be about $70,000 on testing, and the company’s management was ready to throw sharp things at me when I showed up with more budget requests for testing, my personal safety meant that I couldn’t ask for more testing for what, at the time, was a one-off project. I did do some follow up and, once I learned what was required to qualify to bid on the project, vented my frustration on some of the usual suspects, such as Jeff Baker of WestLab. Jeff, among others, educated me in the difficulties in trying to meet the standard by establishing an equivalency between Canadian and European testing methods. Surely, by now, this had been accomplished and the Canadian Passive House Program must have a way to utilize Canadian testing, right?

To update myself, I contacted Cameron Laidlaw, a team lead for technical services at Passive House Canada. Without editing, here is his answer:

Passive House windows are indeed assessed according to various EN and ISO standards. From all of the testing that I have seen and undertaken, there is no easy conversion between the ISO standards and those used for NAFS. Results when the same product is simulated to both don’t return a consistent difference. There are some loose conclusions that can be drawn around when you might expect results to align more closely versus not, but not to the degree that there can be any sort of standardized adjustment factor or conversion, unfortunately. That being said, with the advent of resources like the “Reference Procedure for Determining Window Performance Values for PHPP,” it has become significantly easier for manufacturers to assess their products against the EN/ISO standards, either in-house, or through a third-party consultant.

The reference procedure Cameron mentions is available on the Passive House Canada website passivehousecanada.ca.

Now back to me writing. Above is a reasonable explanation from the Passive House people, but is it valid? Let’s start with a major difference in how windows are tested between North American testing and European testing criteria. In North America, we test with a 21 Celsius internal temperature and a minus 18 C exterior temp. The European testing uses a 20 C internal and a 0 C external. The difference between 21 and 20 C is not a big deal, however the difference between minus 18 and a 0 C is earth-shattering. One can understand why Europe uses 0 C. It is expected to be a temperate climate, so this makes sense. (I say “expected” in deference to the reality that actual temperatures are going crazy due to global warming.) Zero Celsius does not apply to the Canadian climate as a cold condition. The result is that the European test, when applied in Canada, will result in an irrelevant and misleading result.

According to Baker, who knows much more than I on this subject, one design implication of the temperature differential is that North American manufacturers building products actually designed for our climate will opt for air spaces in the 12- to 13-millimeter range. European manufacturers, building to their test standards, will opt for 16 to 17 millimeter air spaces which will not offer peak performance in our climate at our extremely cold temperatures in the dead of winter. When temperatures drop below 0 C, there is a huge drop in performance. Clearly, use of windows based on the European testing model are inferior in our environment to those designed and tested to North American standards.

I did run across a caveat where a window can be used legitimately in a Passive House specification without being tested in the European standard. Here is where I am about to go over my head, so forgive me. If it can be entered in the data flow of the Passive House computer system’s input formula, and if the overall output meets the Passive House requirements, any window meeting the building code could legitimately be used. However, it is unclear to me as to how easy or difficult it is to create a data flow that works.

Another issue which needs to be recognized in Passive House design (and, to be fair, in all designs going forward,) is the potential for overheating. Build a nearly airtight building envelope. Put in high-solar-gain windows. You can, in some instances, create an interior where overheating is significant. I am told that in B.C. some houses with this issue have required retrofitting with air conditioning. The whole issue between high- and low-solar-gain glass is an issue for another article.

The chart above shows the dangers of working with the Passive House program based on their use of a 0 C test exterior. This chart shows that when a product designed to the near-optimum glass spacing for the North American standards at minus 18 C the U-factor will improve (U will decrease) by three percent as the temperature warms to 0 C. A product designed to the near-optimum glass spacing for the Passive House standard at 0 C will degrade (U will increase) by 19 percent when the temperature decreases to minus 18 C. This indicates that when a Passive House window is used in a cold Canadian climate the home owner is not getting the claimed performance of the product.

Why? It’s complicated, but suffice to say that heat passes through a barrier faster when the temperature differential on either side is greater.

My conclusion on having educated myself to the facts and getting scarily technical compared to my usual rants, is that the Passive House Program as it stands, using European test modelling, is inappropriate for the Canadian climate. If the program made some basic changes to its testing procedure and if the ownership of the program recognized the importance of regionalization of testing standards to be appropriate for climate differences, this program could be an asset in the fight against climate change. However, as it now stands, it is inappropriate for use in Canada and should not be specified in its present form. Perhaps Canada’s various certification bodies can put together an alternative program that could be used in a Passive House setting as described by Cameron.

Phil Lewin is technical director for SAWDAC.

Print this page